RESOURCES SERIES: Earthquake-safe Buildings

ARTICLE 24 in a series of Educational Articles for Developing Nations to Improve the Earthquake Safety of Buildings

ABOUT THIS SERIES OF RESOURCES >>

Compared to previous articles, this article takes a broader perspective. It discusses how urban planning can reduce an earthquake’s destructive impact upon a region, city or community. Just like public health initiatives, such as provision of drinking water and sanitation prevent widespread disease, urban planning can reduce the effects of an earthquake and facilitate recovery.

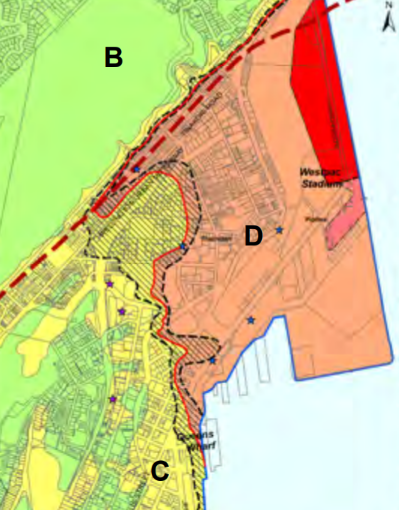

Urban planners need seismic hazard maps to guide development. Such maps identify the presence of active fault zones (which development should avoid at all cost), and areas likely to experience greater shaking due to deep soft soils (Figure 1). These maps also indicate areas prone to liquefaction, landslide or rockfall during earthquake, and to tsunami inundation. With this information, planners can locate essential facilities, like fire stations and hospitals in safe areas and avoid locating housing in unsafe areas. The most hazardous areas might be designated as parks. An online search for “city seismic hazard map” will reveal many examples of these maps from around the world.

Figure 1. A ground shaking map for part of Wellington, New Zealand. Zone B will experience the least intense shaking, followed by C. D signifies the area of almost the worst shaking, with it peaking in the red area (Wellington City Council).

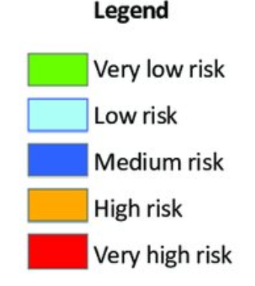

Another useful tool for planners is a seismic vulnerability map. This shows the relative earthquake vulnerability of the building stock in a certain area based on building surveys and engineering analysis (Figure 2). When used in conjunction with a seismic hazard map, geographical distribution of likely earthquake damage can inform the planning process. For example, city authorities might use this information to purchase rows of properties in the most vulnerable areas to increase street widths. This would reduce day-to-day congestion, enhance access by emergency services and provide wider fire breaks in anticipation of post-earthquake fires. Or authorities might require and assist owners of vulnerable buildings to upgrade them to protect a specific precinct of historical importance before it is lost in a large earthquake.

Figure 2. An earthquake vulnerability map of a city showing risk associated with building types and other factors (M. Tafti).

Urban planners need to work as members of interdisciplinary teams that include structural engineers. This is because in the past some cities have introduced regulations that unintentionally lead to buildings that are less earthquake-safe. For example, requirements to increase ground floor parking can result in buildings with soft stories (Article 11), and permission to allow buildings to project out above the footpath into the street can lead to discontinuous walls (Article 12).

References:

Charleson, A. W., 2008. Seismic design for architects: outwitting the quake. Oxford, Elsevier, pp. 233-242.

<< PREVIOUS ARTICLE I NEXT ARTICLE >>

RESOURCES SERIES

INTRODUCTION:

About this resources series

- Earthquakes and How They Affect Us

- Avoiding Soil and Foundation Problems during Earthquakes

- Three Structural Systems to Resist Earthquakes

- Why Walls Are the Best Earthquake-resistant Structural Elements

- Are Walls in Buildings Helpful during Earthquakes?

- How Do Buildings with Reinforced Concrete Columns and Beams Work in Earthquakes?

- Principles for Earthquake-safe Masonry Buildings

- Tying Parts of Buildings Together to Resist Earthquakes

- Local Wisdom and Building Safety in Earthquakes

- Infill Walls and How They Affect Buildings during Earthquakes

- A Common Structural Weakness to Avoid: Soft Story

- A Common Structural Weakness to Avoid: A Discontinuous Wall

- A Common Structural Weakness to Avoid: Short Column

- Preventing a Building from Twisting during Earthquake

- Why Buildings Pound Each Other during Earthquakes

- Construction Codes and Standards

- What to Look for in Building Regulations

- What to Expect from a Building Designed according to Codes

- Importance of Checks during the Design of Buildings

- Importance of Checks during the Construction of Buildings

- Preventing Damage to Non-structural Components

- Retrofitting Buildings against Earthquake

- Advanced Earthquake-Resilient Approaches for Buildings

- Urban Planning and Earthquake Safety

- Tsunamis and Buildings